Tutorial 02

The material for this tutorial was taken from Darren Hoch’s “Linux System and Performance Monitoring”. You can access it at: http://ufsdump.org/papers/oscon2009-linux-monitoring.pdf.

00 Tutorial objectives

- Offer an introduction to I/O and Network monitoring.

- Get you acquainted with a few linux standard monitoring tools and their outputs, for monitoring the impact of the I/Os and Network on the system.

01 Introducing I/O Monitoring

Disk I/O subsystems are the slowest part of any Linux system. This is due mainly to their distance from the CPU and the fact that disks require the physics to work (rotation and seek). If the time taken to access disk as opposed to memory was converted into minutes and seconds, it is the difference between 7 days and 7 minutes. As a result, it is essential that the Linux kernel minimises the amount of I/O it generates on a disk. The following subsections describe the different ways the kernel processes data I/O from disk to memory and back.

Reading and Writing Data - Memory Pages

The Linux kernel breaks disk I/O into pages. The default page size on most Linux systems is 4K. It reads and writes disk blocks in and out of memory in 4K page sizes. You can check the page size of your system by using the time command in verbose mode and searching for the page size: # /usr/bin/time –v date.

Major and Minor Page Faults

Linux, like most UNIX systems, uses a virtual memory layer that maps into physical address space. This mapping is “on demand” in the sense that when a process starts, the kernel only maps what is required. When an application starts, the kernel searches the CPU caches and then physical memory. If the data does not exist in either, the kernel issues a major page fault (MPF). A MPF is a request to the disk subsystem to retrieve pages of the disk and buffer them in RAM.

Once memory pages are mapped into the buffer cache, the kernel will attempt to use these pages resulting in a minor page fault (MnPF). A MnPF saves the kernel time by reusing a page in memory as opposed to placing it back on the disk.

To find out how many MPF and MnPF occurred when an application starts, the time command can be used: # /usr/bin/time –v evolution.

The File Buffer Cache

The file buffer cache is used by the kernel to minimise MPFs and maximise MnPFs. As a system generates I/O over time, this buffer cache will continue to grow as the system as the system will leave these pages in memory until memory gets low and the kernel needs to “free” some of these pages for other uses. The end result is that many system administrators see low amounts of free memory and become concerned when in reality, the system is just making good use of its caches.

Types of Memory Pages

There are 3 types of memory pages in the Linux kernel:

- Read Pages – Pages of data read in via disk (MPF) that are read only and backed on disk. These pages exist in the Buffer Cache and include static files, binaries, and libraries that do not change. The Kernel will continue to page these into memory as it needs them. If the system becomes short on memory, the kernel will “steal” these pages and place them back on the free list causing an application to have to MPF to bring them back in.

- Dirty Pages – Pages of data that have been modified by the kernel while in memory. These pages need to be synced back to disk at some point by the pdflush daemon. In the event of a memory shortage, kswapd (along with pdflush) will write these pages to disk in order to make room in memory.

- Anonymous Pages – Pages of data that do belong to a process, but do not have any file or backing store associated with them. They can't be synchronised back to disk. In the event of a memory shortage, kswapd writes these to the swap device as temporary storage until more RAM is free (“swapping” pages).

Writing Data Pages Back to Disk

Applications themselves may choose to write dirty pages back to disk immediately using the fsync() or sync() system calls. These system calls issue a direct request to the I/O scheduler. If an application does not invoke these system calls, the pdflush kernel daemon runs at periodic intervals and writes pages back to disk.

02 Monitoring I/O

Certain conditions occur on a system that may create I/O bottlenecks. These conditions may be identified by using a standard set of system monitoring tools. These tools include top, vmstat, iostat, and sar. There are some similarities between the outputs of these commands, but for the most part, each offers a unique set of output that provides a different aspect on performance. The following subsections describe conditions that cause I/O bottlenecks.

Calculating IOs Per Second

Every I/O request to a disk takes a certain amount of time. This is due primarily to the fact that a disk must spin and a head must seek. The spinning of a disk is often referred to as “rotational delay” (RD) and the moving of the head as a “disk seek” (DS). The time it takes for each I/O request is calculated by adding DS and RD. A disk's RD is fixed based on the RPM of the drive. An RD is considered half a revolution around a disk. To calculate RD for a 10K RPM drive, perform the following:

- Divide 10000 RPM by 60 seconds (10000/60 = 166 RPS)

- Convert 1 of 166 to decimal (1/166 = 0.006 seconds per Rotation)

- Multiply the seconds per rotation by 1000 milliseconds (6 MS per rotation)

- Divide the total in half (6/2 = 3 MS) (RD is considered half a revolution around a disk)

- Add an average of 3 MS for seek time (3 MS + 3 MS = 6 MS)

- Add 2 MS for latency (internal transfer) (6 MS + 2 MS = 8MS)

- Divide 1000 MS by 8MS per I/O (1000/8 = 125 IOPS)

Each time an application issues an I/O, it takes an average of 8MS to service that I/O on a 10K RPM disk. Since this is a fixed time, it is imperative that the disk be as efficient as possible with the time it will spend reading and writing to the disk. The amount of I/O requests is often measured in I/Os Per Second (IOPS). The 10K RPM disk has the ability to push 120 to 150 (burst) IOPS. To measure the effectiveness of IOPS, divide the amount of IOPS by the amount of data read or written for each I/O.

Go through Ex00

Random vs Sequential I/O

The relevance of KB per I/O depends on the workload of the system. There are two different types of workload categories on a system: sequential and random.

Sequential I/O - The iostat command provides information on IOPS and the amount of data processed during each I/O. Use the –x switch with iostat (iostat –x 1). Sequential workloads require large amounts of data to be read sequentially and at once. These include applications such as enterprise databases executing large queries and streaming media services capturing data. With sequential workloads, the KB per I/O ratio should be high. Sequential workload performance relies on the ability to move large amounts of data as fast as possible. If each I/O costs time, it is imperative to get as much data out of that I/O as possible.

Go through Ex01

Random I/O - Random access workloads do not depend as much on size of data. They depend primarily on the amount of IOPS a disk can push. Web and mail servers are examples of random access workloads. The I/O requests are rather small. Random access workload relies on how many requests can be processed at once. Therefore, the amount of IOPS the disk can push becomes crucial.

When Virtual Memory Kills I/O

If the system does not have enough RAM to accommodate all requests, it must start to use the SWAP device. As file system I/Os, writes to the SWAP device are just as costly. If the system is extremely deprived of RAM, it is possible that it will create a paging storm to the SWAP disk. If the SWAP device is on the same file system as the data trying to be accessed, the system will enter into contention for the I/O paths. This will cause a complete performance breakdown on the system. If pages can't be read or written to disk, they will stay in RAM longer. If they stay in RAM longer, the kernel will need to free the RAM. The problem is that the I/O channels are so clogged that nothing can be done. This inevitably leads to a kernel panic and crash of the system.

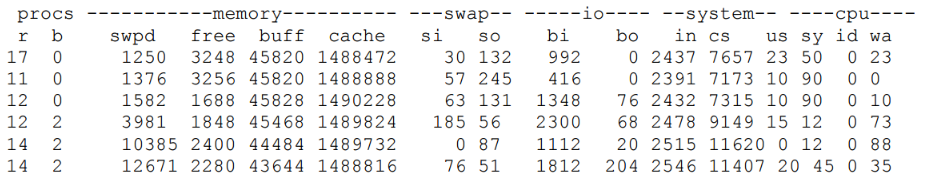

The following vmstat output demonstrates a system under memory distress. It is writing data out to the swap device:

The previous output demonstrates a large amount of read requests into memory (bi). The requests are so many that the system is short on memory (free). This is causing the system to send blocks to the swap device (so) and the size of swap keeps growing (swpd). Also notice a large percentage of WIO time (wa). This indicates that the CPU is starting to slow down because of I/O requests.

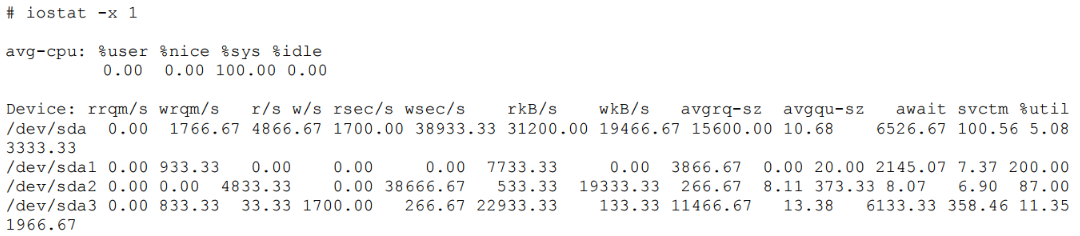

To see the effect the swapping to disk is having on the system, check the swap partition on the drive using iostat.

Both the swap device (/dev/sda1) and the file system device (/dev/sda3) are contending for I/O. Both have high amounts of write requests per second (w/s) and high wait time (await) to low service time ratios (svctm). This indicates that there is contention between the two partitions, causing both to underperform.

Conclusion

Takeaways for I/O monitoring:

- Any time the CPU is waiting on I/O, the disks are overloaded.

- Calculate the amount of IOPS your disks can sustain.

- Determine whether your applications require random or sequential disk access.

- Monitor slow disks by comparing wait times and service times.

- Monitor the swap and file system partitions to make sure that virtual memory is not contending for filesystem I/O.

03 Introducing Network Monitoring

Out of all the subsystems to monitor, networking is the hardest to monitor. This is due primarily to the fact that the network is abstract. There are many factors that are beyond a system’s control when it comes to monitoring and performance. These factors include latency, collisions, congestion and packet corruption to name a few.

This section focuses on how to check the performance of Ethernet, IP and TCP.

Ethernet Configuration Settings

Unless explicitly changed, all Ethernet networks are auto negotiated for speed. The benefit of this is largely historical when there were multiple devices on a network at different speeds and duplexes.

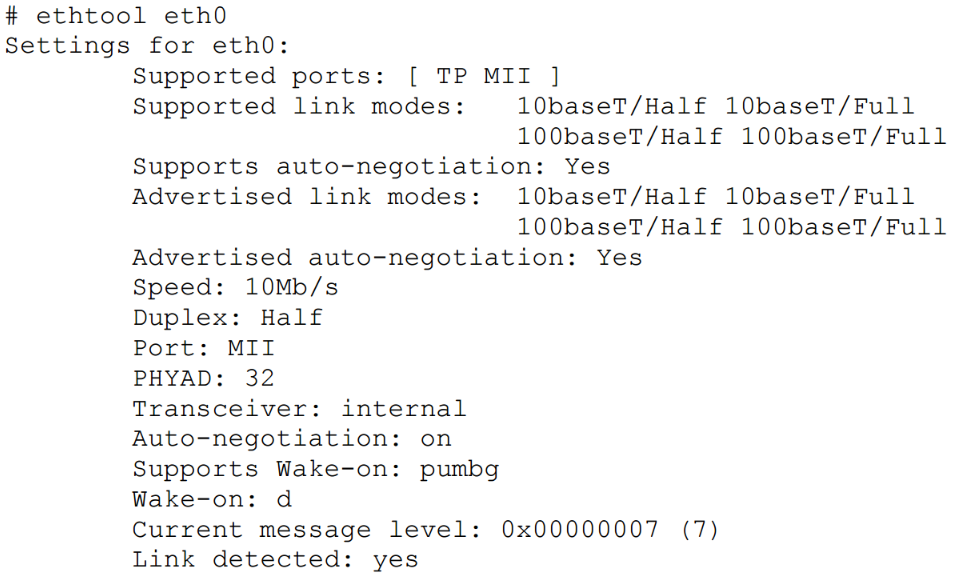

Most enterprise Ethernet networks run at either 100 or 1000BaseTX. Use ethtool to ensure that a specific system is synced at this speed.

In the following example, a system with a 100BaseTX card is running auto negotiated in 10BaseT.

The following command can be used to force the card into 100BaseTX: # ethtool -s eth0 speed 100 duplex full autoneg off.

Monitoring Network Throughput

It is impossible to control or tune the switches, wires, and routers that sit in between two host systems. The best way to test network throughput is to send traffic between two systems and measure statistics like latency and speed.

Using iptraf for Local Throughput

The iptraf utility (http://iptraf.seul.org) provides a dashboard of throughput per Ethernet interface. (Use: # iptraf –d eth0)

Using netperf for Endpoint Throughput

Unlike iptraf which is a passive interface that monitors traffic, the netperf utility enables a system administrator to perform controlled tests of network throughput. This is extremely helpful in determining the throughput from a client workstation to a heavily utilised server such as a file or web server. The netperf utility runs in a client/server mode.

To perform a basic controlled throughput test, the netperf server must be running on the server system (server# netserver).

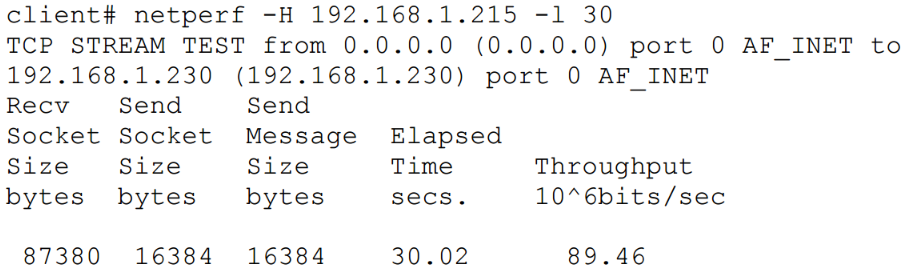

There are multiple tests that the netperf utility may perform. The most basic test is a standard throughput test. The following test initiated from the client performs a 30 second test of TCP based throughput on a LAN. The output shows that that the throughput on the network is around 89 mbps. The server (192.168.1.215) is on the same LAN. This is exceptional performance for a 100 mbps network.

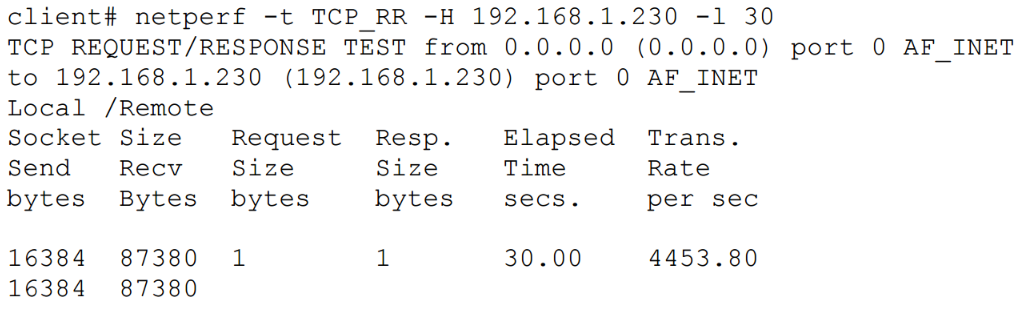

Another useful test using netperf is to monitor the amount of TCP request and response transactions taking place per second. The test accomplishes this by creating a single TCP connection and then sending multiple request/response sequences over that connection (ack packets back and forth with a byte size of 1). This behavior is similar to applications such as RDBMS executing multiple transactions or mail servers piping multiple messages over one connection.

The following example simulates TCP request/response over the duration of 30 seconds.

In the previous output, the network supported a transaction rate of 4453 psh/ack per second using 1 byte payloads. This is somewhat unrealistic due to the fact that most requests, especially responses, are greater than 1 byte.

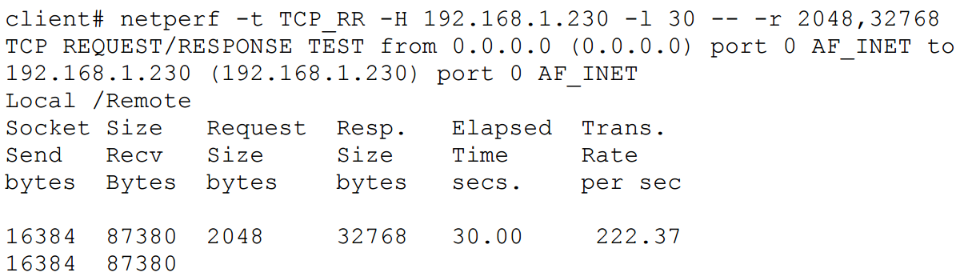

In a more realistic example, a netperf uses a default size of 2K for requests and 32K for responses.

The transaction rate reduces significantly to 222 transactions per second.

Using iperf to Measure Network Efficiency

The iperf tool is similar to the netperf tool in that it checks connections between two endpoints. The difference with iperf is that it has more in-depth checks around TCP/UDP efficiency such as window sizes and QoS settings. The tool is designed for administrators who specifically want to tune TCP/IP stacks and then test the effectiveness of those stacks. The iperf tool is a single binary that can run in either server or client mode. The tool runs on port 5001 by default. In addition to TCP tests, iperf also has UDP tests to measure packet loss and jitter.

Individual Connections with tcptrace

The tcptrace utility provides detailed TCP based information about specific connections. The utility uses libpcap based files to perform an analysis of specific TCP sessions. The utility provides information that is at times difficult to catch in a TCP stream. This information includes:

- TCP Retransmissions – the amount of packets that needed to be sent again and the total data size

- TCP Window Sizes – identify slow connections with small window sizes

- Total throughput of the connection

- Connection duration

For more information refer to pages 34-37 from Darren Hoch’s “Linux System and Performance Monitoring” - http://ufsdump.org/papers/oscon2009-linux-monitoring.pdf.

Conclusion

Takeaways for network performance monitoring:

- Check to make sure all Ethernet interfaces are running at proper rates.

- Check total throughput per network interface and be sure it is inline with network speeds.

- Monitor network traffic types to ensure that the appropriate traffic has precedence on the system.

Exercices

Ex00

- Calculate the rotational delay (RD) for a 5400 RPM drive

Ex01

- Run iostat –x 1 5

- Considering the last two outputs provided by the previous command, calculate the efficiency of IOPS for each of them. Does the amount of data written per I/O increase or decrease?

Hint

- Divide the kilobytes read (rkB/s) and written (wkB/s) per second by the reads per second (r/s) and the writes per second (w/s).

Ex02

- Create a 16GB file of random generated integers ranging from 1 to 10 million.

- Write a script to sort the numbers in this file in ascending order.

- Monitor the system performance using the tools presented in this tutorial.

Hint

- Split the file into smaller chunks that would fit in memory (e.g. 4GB).

- Use a classical sort algorithm for sorting these chunks.

- Merge the sorted chunks two by two. Read in memory only two numbers at a time (one from each chunk) starting from the beginning, compare the numbers, write the smallest in the merged file, and read the next number from the chunk that had its number written in the merged file.

- Repeat the last step until you obtain the original file sorted.