This is an old revision of the document!

Lab 11

Lab 01 - Web Basics

The web is the backbone of the internet, and the largest application platform today. This is all due to a core characteristic:

The web is simple.

Think about it - when you want to check Facebook, you just type facebook.com in your browser, press Enter, *poof* and you suddenly know what all your friends ate this morning. This simplicity isn't apparent - although there are some complex things going on, most of the behind-the-scenes stuff is pretty easy to understand.

This lab aims to help you learn the bare minimum that you need to know in order to develop a website. You'll see how the browser works, you'll learn how the server knows what data to send, and you'll find out how designers make websites look pretty.

here] **//Let's dig in!//** ====== 🌍 The browser ====== > A **web browser** (commonly referred to as a browser) is a software application for accessing information on the World Wide Web. Each individual web page, image, and video is identified by a distinct URL, enabling browsers to retrieve and display them on the user's device. That's [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_browser|Wikipedia's definition of a web browser. Pretty boring, ain't it ? Let's define it a different way:

A web browser is the vehicle that allows you to view, interact and discover everything from what's going on in the USA to some guy that loves hats.

We all know how to use a web browser - you're using it right now to view this page. You probably also have other pages open in the background, such as YouTube or Facebook. Some of those pages might send you notifications, or play media content such as video and audio. But what exactly makes it tick ?

How does the browser know what to render

If you hit Ctrl + U in this page, you'll see something similar to this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en" class="no-js">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1">

<meta http-equiv="x-ua-compatible" content="ie=edge">

<meta name="lang:search.language" content="en">

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="../../assets/images/favicon.png">

<meta name="generator" content="mkdocs-0.17.3, mkdocs-material-2.8.0">

<title>Browser - .js Summer Course</title>

............................................................................

This code is called HTML, and is the language that defines the “scaffolding” of any webpage. We'll dive into HTML later, but for now you only need to know that the elements that are between <> brackets (like <meta>) are called tags, and are the building blocks of the language.

HTML and its tags define a tree, which represents the structure of our web page. That is why we call it our “scaffolding”: it builds our page like a resistance structure builds a house.

If you dive deeper into the source code of any webpage, you'll come across something like this:

.md-nav__title { display: inline-block; margin: .4rem; padding: .8rem; font-size: 2.4rem; cursor: pointer }

This is HTML's counterpart, CSS. While HTML defines our page's structure, CSS tells the browser how elements are supposed to look. We'll look into CSS in depth a bit later.

How does rendering actually happen ?

The page rendering process is broken up into multiple steps, as shown in this diagram:

If you follow the pipeline above, you'll see that the steps are more or less as follows. We'll ignore the Script blocks for now.

- Parse HTML and generate the page structure tree (we call this the DOM, or the Document Object Model)

- At the same time, parse any CSS we have and create the style structure (this is called the CSSOM, a counterpart tree of the DOM that tells us how each element should look)

- After we have both the DOM and the CSSOM, we match the nodes in each tree and begin rendering and displaying on the screen.

There are a few extra steps in the pipeline such as reflow / layout, paint and composite, but all you really need to follow in the image above are the blue and purple boxes.

Examples

A visualisation of this process for an older version of the Twitter site:

As you can see, the browser first positions the elements in the top-left corner of the parent element (most of the time this is the browser window), renders the contents, applies the required CSS and then positions the element correctly in the page.

Another visualisation of a more complex website is here:

Notice how the browser begins to render a lot of elements between 0:20 and 1:30 ? Those are the individual options available in the dropdown menus (day, month, year) that we need to have ready to display when the user toggles the dropdown.

As you can see, the browser does a huge amount of work in a short amount of time in order to present you a website. And this is just the structure and painting - we haven't gotten to interactivity yet.

For a more in-depth look at how the browser renders our page, check out this talk by Ryan Seddon at JSConf EU 2015:

Also, if you are interested in learning more about the specifics of how the browser renders a page, check out this artucle from Mozilla Hacks.

💫 HTTP and APIs

We've seen how the browser renders the page that we see, but how do the files get from the server to our browser, in order to be rendered ?

The magic behind this is a protocol called HTTP. Let's see what MDN has to say about HTTP:

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is an application-layer protocol for transmitting hypermedia documents, such as HTML. … HTTP is a stateless protocol, meaning that the server does not keep any data (state) between two requests.

Let's break this definition down:

- application-layer protocol - this just means that is a protocol intended to be used by an application (e.g. a browser, a server, etc.) as opposed to a protocol intended to use by hardware devices

- hypermedia documents - hypermedia is a term extended from hypertext, and basically means any text and media (e.g. images, videos) that can be linked using hyperlinks (URLs)

- stateless protocol - as the rest of the definition says, this means that the server doesn't keep any state between two requests. In real life use, this means that HTTP provides no way for the server to know that a request is part of a longer chain of requests, or that a specific request is associated to an user.

Although it might seem daunting at first, you'll see that HTTP is a very simple, text-based protocol. Communication in HTTP is request-response based: the client sends the server a request, and the server replies with a response. There are a few extra cases, but most of the time this is the way the protocol works.

The protocol only specifies a couple of things, the most important being the format of the request and the response.

The HTTP Request and Response formats

When the client makes a request to a server, the packet it sends needs to have the following fields:

- A

requestline - Zero or more

headerfields - An empty line

- An optional message body

A complete request looks something like this:

GET /hello.html HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE5.01; Windows NT) Host: www.facebook.com Accept-Language: en-us Accept-Encoding: gzip

The following line:

GET /hello.html HTTP/1.1

is the request line. This specified the HTTP method (GET), the resource we want to request (/hello.html) and the protocol version that we are using (HTTP/1.1).

A resource in HTTP terms is any object that we can manipulate on a server. This is usually a text file (HTML, CSS, etc.) but can also be dynamic media such as images, photos or video streams.

The rest of the lines in the request are the header fields. These have the format of Key: Value, and are always entered each on one line. There are two more interesting header fields in the request above:

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE5.01; Windows NT) Host: www.facebook.com

The first line tells the server a bit about the client that is sending the request. In this way, the server can, for example, send plaintext metadata about an image if the requester is a command-line browser, and send the complete media file if the server is a graphical one.

The next line specifies the host that we are connecting to. The resource path in the request line is relative to the Host value.

The following lines are examples that set various parameters about the client so that the server has an easier time sending a correct response.

An HTTP response looks similar to the request. The required information that the server has to include is:

- A

statusline - Zero or more header fields

- An empty line

- Optionally, a message body

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Mon, 27 Jul 2009 12:28:53 GMT Server: Apache/2.2.14 (Win32) Last-Modified: Wed, 22 Jul 2009 19:15:56 GMT Content-Length: 88 Content-Type: text/html Connection: Closed

Here we can see fields such as Date and Server that tell us information about the server, Last-Modified and Content-Length that tell us information about the content we have requested, and more.

The most important part of the response though is the very first line:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

This tells us the HTTP version (which usually matches the one the client sends in its request) but also the status code and its meaning.

HTTP Status Codes

In order for the server to inform us about how the request went, HTTP specifies a Status Code directive. These codes are numerical values ranging from 100 to 500 that have associated human-readable strings to explain what went wrong (or right) with the request. These codes are categorized based on the first number in the code:

- 🔵 1xx codes Informational codes. These codes usually tell us that the request has been received and we must wait.

- ✅ 2xx codes Success codes. These codes confirm that the request was completed without problems.

- 💫 3xx codes Redirection codes. These codes tell us that we must do something else (such as make another request at a different address) in order to complete the operation.

- 💬 4xx codes Client error codes. These codes mean that the request that we sent was wrong or cannot be fulfilled for some reason.

- ⛔ 5xx codes Server error codes. These codes mean that the server had trouble fulfilling our request

Most of the time you'll only interact with a couple of codes:

| Code | Message | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | OK | Request fullfilled successfully |

| 301 | REDIRECT | You'll find what you're looking for at a different address |

| 404 | NOT FOUND | What you requested isn't on this server |

| 500 | SERVER ERROR | The server failed to deliver your request |

HTTP Methods

Apart from status codes, the HTTP protocol also defines a couple of methods used to communicate with the server. Think of these as remote functions that you call on a server. Although the protocol defines many methods, in daily use we only need a couple of these:

- GET - Requests a resource from the server (e.g.

GET /index.html) - POST - Adds a new resource to the server (e.g.

POST /users/new) - PUT - Edits a resource from the server (e.g.

PUT /users/ion) - DELETE - Deletes a resource from the server (e.g.

DELETE /users/andrei)

PUT and POST accept message bodies that detail, for example, how exactly a resource is to be edited, or what the new resource should contain. The GET and DELETE requests usually get all their information from the resource's location.

The browser usually makes GET requests when retrieving web pages, but it also makes POST requests when, for example, you submit an online form.

What is an API ?

An API is simply an HTTP server that, instead of responding with HTML, CSS and JS files, accepts and responds with data-specific formats such as JSON or XML. Most of today's online APIs use JSON as their format of choice. They usually are documented and are intended to be used by software programs.

APIs that respect the HTTP method descriptions above are called REST APIs, or Representational State Transfer APIs.

✨ The languages of the web

We've seen how the browser renders a page, and we've seen how the browser interacts with the server in order to provide us with all that the web offers us. Now, let's dive in a bit deeper and see how exactly do these languages work.

HTML

HTML is the language that defines a web page's structure. As we've seen, HTML uses tags and attributes in order to define a webpage. A simple HTML page example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is a Heading</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

</body>

</html>

We can see here a couple of elements:

- The

<!DOCTYPE html>declaration - this defines the document as a HTML5 file - The

<html>element - this is the root element of the document, similar to how/is the root folder in a Linux filesystem - The

<head>element - this element contains information about the document, such as the page's<title> - The

<body>element - this element contains everything that is visible on the page

HTML tags are standard and describe well-defined elements, for example:

<p>- defines a paragraph box.<div>- defines a generic element that can contain anything<h1>- defines a title (heading)

There are also more specific tags, such as <article> or <nav>. It is important to learn the correct HTML tags to use, as these help the browser and automated tools (such as search engines) make correct assertions about our page.

Some HTML tags also support attributes. You can think of attributes as being similar to function parameters. For example, to embed an image we can use a code that looks like this:

<img src='https://comotion.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/image.jpg' />

Here we are using the img tag's src attribute to specify the source of the image, or, in other words, where is the image located. The browser will then go ahead and retrieve the image, and display it for us.

But let's say that we want to make that image have rounded corners, or be centered, or have a shadow. How would we do that ?

CSS

CSS, standing for Cascading Style Sheet, is the language we use to specify how an element will look like. CSS is a simple language, and it looks something like this:

html { margin: 0; padding: 0; background-color: red; } body { font-size: 16px; font-family: 'Segoe UI', sans-serif; }

As you can see, we pick an HTML tag and say what properties it should have. We define things such as the size of the font, or background color, or spacing between it and other elements.

Classes

We've seen that, in CSS, we can apply rules to elements based on their tag. For example, this rule:

div { background-color: red }

will make all the div elements on the page have a red background color.

But what if we want to target a specific element ? That's where the class attribute comes in - it allows us to select all elements that have that specific class. For example, given this HTML code:

<div> <p> I am a paragraph </p> <p class='red'> I have red text color </p> </div>

We can make the second paragraph have the text color red by applying these CSS rules:

.red { color: red }

This will result in something like this:

I am a paragraph

I have red text color

You can also be more explicit, and specify that a certain rule should only be applied to paragraph tags with the .red class that are under a div tag:

div .red { color: red; }

With the following HTML, this is the result that will appear:

<div> <p class='red'> I have red text color </p> </div> <p class='red'> I have red class but no red text color </p>

<p style="color: red"> I have red text color </p>

I have red class but no red text color

The Box Model

CSS relies on what is called a box model. When we say that the HTML tags are rendered as boxes, these boxes have certain properties that define how they relate to elements around them. An easy way to view the box model is this graphic that you can find in most browser's developer tools menu:

There are four basic components of a box:

- The

widthandheight- these define the baseline size of the element - The

padding- this defines the spacing between the element's contents and its effective border - The

border- this defines the separation between an element's content and the spacing around it - The

margin- this defines the spacing around the element

In CSS, you can define them exactly as written above: width, height etc. You can also specify border, margin or padding for just one side of the box, like so:

padding-top: 5px; padding-right: 4px; padding-bottom: 3px; padding-left: 2px;

Or you can use a shorthand form and define them all in one go:

padding: 5px 4px 3px 2px; | | | | |---|---|---|---- top |---|---|--------- right |---|--------------- bottom |---------------------- left

Animations!

CSS also allows us to animate HTML elements. Let's bring back the photo above:

If we take a look at the CSS applied to the image, we get a hint on how CSS animations work:

.image-css-example .animated { animation-name: image-animation-example; animation-duration: 2s; animation-iteration-count: infinite; } @keyframes image-animation-example { from { border-radius: 0; transform: scale(1); opacity: 1; } 50% { border-radius: 100px; transform: rotate(180deg); opacity: 0; } }

As you can see, we use a couple of rules:

animation-name- this tells the browser what animation rules to useanimation-duration- this is evident - the duration that the animation will run foranimation-iteration-count- this defines the number of times the animation will repeat

These three rules are the bare minimum needed in order to add an animation to a HTML element. But we still need to define how the animation will look like. We do this by using a @keyframes declaration, followed by the animation name (the one we set in the animation-name property).

The body of the @keyframes declaration defines the animation steps. These steps can be:

fromorto- this defines the initial and final state of the object- a percentage - this percentage is the part of the animation, for example 50% is the middle of the animation

We can use the transform property to manipulate an element in various ways, such as:

scale()- makes the item bigger or smallerrotate()- rotates the item clockwise or counterclockwisetranslateX(),translateY(),translateZ()- moves the element in 3D space

You can see more examples of the transform property here.

Defining the animation origin point

By default the origin point of the animation is at the center:

But what if we want to obtain something like this ?

It's simple: we use a rule called ''%%transform-origin%%'':

transform-origin: 0 50%;

This rule takes two parameters: the first represents the horizontal distance from the top left corner, and the second represents the vertical distance from the same corner.

JavaScript

JavaScript is the programming language of the web. It runs in the browser, as well as on the server, and even on Arduino-like hardware. The syntax of JavaScript is very similar to C++, with a few small differences. Here's a small example:

let iceCream = 'chocolate' if (iceCream === 'chocolate') { alert('Yay, I love chocolate ice cream!') } else { alert('Awwww, but chocolate is my favorite...') }

A couple of things are worth mentioning about JavaScript:

- Java has no relation to JavaScript. The name was just an unfortunate market-based decision made by Netscape in the early years of the language.

- As opposed to other languages such as C++ or Java, JavaScript has no types - any variable can take any value. The following is valid JavaScript code:

let x = 1 console.log(x) // prints 1 x = 'hello' console.log(x) // prints 'hello'

- You'll see a lot of code examples on the internet using

varfor variable declarations. We recommend that you uselet. If you want to learn more about the why, read this great article from hackernoon. - You don't need any development environment to write JavaScript - you only need your browser and a simple text editor such as Notepad! Of course, a better text editor such as Visual Studio Code or Atom will improve your experience greatly.

- Semicolons in JavaScript are optional. We recommend using something like prettier-standard paired with an editor such as Visual Studio Code when developing in JavaScript.

We will delve deeper into JavaScript in the lab.

jQuery is not JavaScript

A common mistake is to mix jQuery with JavaScript. This is caused by historic reasons and poor online documentation. What you need to know is that jQuery is written in JavaScript. It's just a library that provides extra APIs for interacting with the browser. In the early days of the internet, where each browser had a slightly different syntax, jQuery was necessary, but nowadays it's more of an impediment rather than a useful thing to use.

GitHub Pages

Tasks

Task 1 - Modify the task.css file from Task 1 to make the human do something (e.g. jump).

Task 2 - Create a personal page and host it using GitHub Pages. Here are two examples of personal pages:

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 02 - Javascript

✨ Intro

JavaScript is the programming language of not only the browser, but also the server, native applications and even Arduino boards!

In the browser

JavaScript in the browser has many uses:

- you can add event listeners and run code based on certain things happening - the user moving a mouse, clicking a button or resizing the window

- you can interact and change HTML nodes from simple things such as changing their content up to completely generating a page using only JavaScript. That's how modern web frameworks such as React.js work!

- you can make network requests and access resources on other websites

- you can send native notifications with various content

- you can control media such as audio on a page

And many, many more things. We'll go through each one of these things in the tasks, but first let's see how the language looks like.

JavaScript language basics

JavaScript is a language that looks very similar to languages that you might have used in the past, such as Java, C++ or Racket. As you'll see, some concepts are indeed very similar, although some things are a bit different.

Variables: let vs const vs var

In JavaScript there are three ways to declare a variable:

let x = 'hello'const y = "I won't change"var z = 'never use me like this'

JavaScript doesn't have types - this means that a variable can take a value of any type, and can change types at will. This gives us a great deal of flexibility when working with the language. For example, the following is a valid JavaScript code:

let x = 'I am a string' x = 5 + 5

In the list above we also see the const variable type. As you might expect, this type of variable is a constant, and its value won't change. For example, this code will fail:

const x = 5 x = 6 // Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

Constants are very useful when we want to ensure that a certain variable won't change (like in C, where we declare global constants) or when we want to maintain the answer from a certain function untouched.

Semicolons are optional

JavaScript does something called Automatic Semicolon Insertion. This feature means that we don't have to worry about semicolons, as the JavaScript interpreter will insert them automatically, but we can also use them if we feel like it.

Why is var so introverted ?

You may have noticed that var above isn't the most friendly type. This is because var isn't scope-limited, and this can cause some nasty things. For example, var allows you to declare the same variable twice:

var x = 5 var x = undefined console.log(x) // Prints 'undefined'

var also does some nasty things such as not being block scoped, which can cause a whole lot of problems, but we won't deal with those as they are not our focus here.

The moral here is simple: > #*** Don't use var! ***

Special values

As in any language, there are a couple of values that you might see around and that have a special meaning to them:

undefined- this means that the variable has been declared but not initialized (let x)

var x console.log(x) // undefined

NaN- stands for not a number. This is set when doing invalid conversion operations:

let x = 'hello' * 3 console.log(x) // NaN

null- returned from some functions when no response can be given.

let x = 'hello'.match('bye') console.log(x) // null

Functions

Functions in JavaScript have a couple of interesting properties:

- they can take any number of arguments

- they can be passed around as variables

- they can be declared as variables

- they can be called asynchronously

Functions are usually declared in one of two ways:

- With the

functionkeyword:

function add (a, b) { return a + b }

- As an arrow function:

let sum = (a, b) => a + b

Arrow functions are a more compact form of writing a function, without declaring it explicitly. They have some interesting properties:

- if they have only one argument, the parantheses can be omitted:

let inc = a => a + 1

- they return anything that's after the arrow if there are no brackets:

let withoutBrackets = (a, b) => a + b let withBrackets = (a, b) => { let sum = a + b } console.log(withoutBrackets(1,2)) // logs 3 console.log(withBrackets(1,2)) // logs undefined because we // don't return anything

Callbacks

A function that is passed as a parameter is usually called a callback. This is because that function is usually called back at a later time. For example:

function sayHi () { console.log('Hi!') } function iHaveACallback(callback) { setTimeout( () => callback(), // The function we want to call 1000 // Miliseconds to wait before calling the function ) } iHaveACallback(sayHi) // Will print 'Hi!' after 1 second

Try running the code above in your browser's developer console and see what happens.

Network requests using fetch

In order to do network requests, we're going to use the Fetch API. This API is based on Promises. It looks weird at first, but promises are just another way to write callback functions. For example, a simple Fetch request looks like this:

fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/1') // Make a GET request .then(response => response.json()) // Treat the response as JSON .then(json => console.log(json)) // Prints a JSON object .catch(e => console.log('Uh oh! An error occured'))

You can see that the Fetch promise has three parts:

fetch('https:...')- This is the main call of the function. It specifies the URL we want to request.then(...)- This function specifies what we do after the request is done. We can have multiple chainedthencalls, and each function sent as a parameter will get the previous function's return value.catch- This function will run whenever an error occurs

Browser APIs

The browser allows us to use JavaScript in order to interact with the DOM. Let's see how we can do some simple operations with it!

Manipulating the DOM

We can manipulate the DOM by using functions available in the document global object:

const body = document.querySelector('body') // Get the page body, or any other HTML element let testDiv = document.createElement('div') // Creates a div element testDiv.textContent = 'I am a new div!' // Set the inner content of a div body.appendChild(testDiv) // Adds the div as a child to the page

Try running the code above on a blank page and see what happens!

Event listeners

Apart from adding elements to the DOM, we can also listen to certain events. For example, assuming we have this HTML:

<body>

<div class='clickme'>

Click me!

</div>

</body>

We can use the following JavaScript code to trigger a message to the user when the div is clicked:

let div = document.querySelector('.clickme') // Get the Div div.addEventListener('click', () => alert('Hello!))

Tasks

For today, you'll going to have to do the following:

- Download the zip file containing the tasks.

- Go to the tasks/ folder, and complete all the functions marked with TODO: in the index.js file

- In the api/ folder, you have the necessary functions of a command line API client for the typicode API. Fill in the functions and make it work by calling the addPost, getPosts and deletePost functions from the browser's command line

- In the apiInterface/ folder, you will have to reuse the api/ files in order to make a Postman-like interface for the API. Add event listeners to the buttons and output the result from the API in the div in the HTML.

- In the imageGif/ folder, you have an array of image locations and an img object. Can you make a GIF out of them?

- Optional: In the notifyMe/ folder, you already have a setup for a notification request. Trigger a notification when pressing the button.

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 03 - Introduction to React

React

React is a modern Javascript library for building user interfaces.

- React makes it easier to create modern interactive UIs. React adheres to the declarative programming paradigm, you can design views for each state of an application and React will update and render the components when the data changes. This is different than imperative programming (Javascript).

- Component-Based: Components are the building blocks of React, they allow you to split the UI into independent, reusable pieces that work in isolation. Data can be passed through components using “props”.

React Virtual DOM

When new elements are added to the UI, a virtual DOM, which is represented as a tree, is created. Each element is a node on this tree. If the state of any of these elements changes, a new virtual DOM tree is created. This tree is then compared or “diffed” with the previous virtual DOM tree.

Once this is done, the virtual DOM calculates the best possible method to make these changes to the real DOM. This ensures that there are minimal operations on the real DOM. Hence, reducing the performance cost of updating the real DOM.

The red circles represent the nodes that have changed. These nodes represent the UI elements that have had their state changed. The difference between the previous version of the virtual DOM tree and the current virtual DOM tree is then calculated. The whole parent subtree then gets re-rendered to give the updated UI. This updated tree is then batch updated to the real DOM.

JSX

JSX is an XML-like syntax extension to ECMAScript without any defined semantics.

React embraces the fact that rendering logic is inherently coupled with other UI logic: how events are handled, how the state changes over time, and how the data is prepared for display.

Instead of artificially separating technologies by putting markup and logic in separate files, React separates concerns with loosely coupled units called “components” that contain both.

const element = <h1>Hello, world!</h1>;

In the example below, we declare a variable called name and then use it inside JSX by wrapping it in curly braces:

const name = 'Andrei'; const element = <h1>Hello, {name}</h1>;

Components

User interfaces can be broken down into smaller building blocks called components.

Components allow you to build self-contained, reusable snippets of code. If you think of components as LEGO bricks, you can take these individual bricks and combine them together to form larger structures. If you need to update a piece of the UI, you can update the specific component or brick.

This modularity allows your code to be more maintainable as it grows because you can easily add, update, and delete components without touching the rest of our application. The nice thing about React components is that they are just JavaScript.

In React, components are functions or classes, we are only going to use functions. Inside your script tag, write a function called header:

export default function StartupEngineering() { return <div>StartupEngineering</div>; }

Nesting Components

Applications usually include more content than a single component. You can nest React components inside each other like you would do with regular HTML elements.

The <Header> component is nested inside the <HomePage> component:

function Header() { return <h1>Startup Engineering</h1>; } function HomePage() { return ( <div> {/* Nesting the Header component */} <Header /> </div> ); }

Props

Similar to a JavaScript function, you can design components that accept custom arguments (or props) that change the component’s behavior or what is visibly shown when it’s rendered to the screen. Then, you can pass down these props from parent components to child components. Props are read only.

In your HomePage component, you can pass a custom title prop to the Header component, just like you’d pass HTML attributes. Here, titleSE is a custom argument (prop).

function HomePage({titleSE}) { return ( <div> <Header title={titleSE} /> </div> ); }

Conditional Rendering

We’ll create a Greeting component that displays either of these components depending on whether a user is logged in:

function Greeting(props) { const isLoggedIn = props.isLoggedIn; if (isLoggedIn) { return <h1>Welcome back!</h1>; } return <h1>Please sign up.</h1>; }

We can also use inline if-else operators.

When sending props from parent to child component, we can use object destructuring . Destructuring really shines in React apps because it can greatly simplify how you write props.

function Header({ title }) { return <h1>{title ? title : 'Default title'}</h1>; }

Iterating through lists

It’s common to have data that you need to show as a list. You can use array methods to manipulate your data and generate UI elements that are identical in style but hold different pieces of information.

function HomePage() { const names = ['POLI', 'ASE', 'UNIBUC']; return ( <div> <Header title="Universities" /> <ul> {names.map((name) => ( <li key={name}>{name}</li> ))} </ul> </div> ); }

Keys help React identify which items have changed, are added, or are removed. Keys should be given to the elements inside the array to give the elements a stable identity.

The best way to pick a key is to use a string that uniquely identifies a list item among its siblings. Most often you would use IDs from your data as keys.

const universitiesItems = universities.map((uni) => <li key={uni.id}> {uni.name} </li> );

Adding Interactivity with State

React has a set of functions called hooks. Hooks allow you to add additional logic such as state to your components. You can think of state as any information in your UI that changes over time, usually triggered by user interaction.

You can use state to store and increment the number of times a user has clicked the like button. In fact, this is what the React hook to manage state is called: useState()

useState() returns an array. The first item in the array is the state value, which you can name anything. It’s recommended to name it something descriptive. The second item in the array is a function to update the value. You can name the update function anything, but it's common to prefix it with set followed by the name of the state variable you’re updating. The only argument to useState() is the initial state.

function HomePage() { // ... const [likes, setLikes] = React.useState(0); function handleClick() { setLikes(likes => likes + 1); } return ( <div> {/* ... */} <button onClick={handleClick}>Likes ({likes})</button> </div> ); }

Data Binding

Data Binding is the process of connecting the view element or user interface, with the data which populates it.

In ReactJS, components are rendered to the user interface and the component’s logic contains the data to be displayed in the view(UI). The connection between the data to be displayed in the view and the component’s logic is called data binding in ReactJS.

export default function HomePage() { const [inputField, setInputField] = useState(''); function handleChange(e) { setInputField(e.target.value); } return ( <div> <input value={inputField} onChange={handleChange}/> <h1>{inputField}</h1> </div> ); }

Passing data from child to parent component

In react data flows only one way, from a parent component to a child component, it is also known as one way data binding. While there is no direct way to pass data from the child to the parent component, there are workarounds. The most common one is to pass a handler function from the parent to the child component that accepts an argument which is the data from the child component. This can be better illustrated with an example.

const Parent = () => { const [message, setMessage] = React.useState("Hello World"); const chooseMessage = (message) => { setMessage(message); }; return ( <div> <h1>{message}</h1> <Child chooseMessage={chooseMessage} /> </div> ); }; const Child = ({ chooseMessage }) => { let msg = 'Goodbye'; return ( <div> <button onClick={() => chooseMessage(msg)}>Change Message</button> </div> ); };

The initial state of the message variable in the Parent component is set to ‘Hello World’ and it is displayed within the h1 tags in the Parent component as shown. We write a chooseMessage function in the Parent component and pass this function as a prop to the Child component. This function takes an argument message. But data for this message argument is passed from within the Child component as shown. So, on click of the Change Message button, msg = ‘Goodbye’ will now be passed to the chooseMessage handler function in the Parent component and the new value of message in the Parent component will now be ‘Goodbye’. This way, data from the child component(data in the variable msg in Child component) is passed to the parent component.

Tasks

- Download the generated project se-lab3-tasks.zip (amd run npm install and npm run dev)

- Create a to do list app:

- Implement the List component in component/List.js

- Create a new component in components/ that will represent a todo-list item that should have

- text showing the description of the todo-list item

- delete button that emits an event to parent to remove the item

- Create an input that you will use to create new list items by appending to your array

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 04 - React: Forms and APIs

Introduction

In this lab we are going to get comfortable working with forms and public APIs.

An HTML form element represents a document section containing interactive controls for submitting information. In the example below we created a simple form containing only one input representing a Name.

<form> <label> Name: <input type="text" name="name" /> </label> <input type="submit" value="Submit" /> </form>

Controlled Components

In React, Controlled Components are those in which form’s data is handled by the component’s state. It takes its current value through props and makes changes through callbacks like onClick,onChange, etc. A parent component manages its own state and passes the new values as props to the controlled component.

In the form elements are either the typed ones like textarea, input or the selected one like radio buttons or checkboxes. Whenever there is any change made it is updated accordingly through some functions that update the state as well.

export default function Form() { const [name, setName] = React.useState(''); function handleChange(event) { setName(name => event.target.value); } function handleSubmit(event) { alert('A name was submitted: ' + name); event.preventDefault(); } return ( <form onSubmit={handleSubmit}> <label> Name: <input type="text" value={name} onChange={handleChange} /> </label> <button type="submit" value="Submit" /> </form> ); }

In most cases it is recommended to use Controlled Components to implement forms.

preventDefault()

By default, the browser will refresh the page when a form submission event is triggered. We generally want to avoid this in React.js applications because it would cause us to lose our state.

To prevent the default browser behavior, we have to use the preventDefault() method on the event object.

function handleSubmit(event) { alert('A name was submitted: ' + name); event.preventDefault(); }

Text Area

A <textarea> element in HTML:

<textarea> DSS rules! </textarea>

In React, a <textarea> uses a value attribute instead. This way, a form using a <textarea> can be written very similarly to a form that uses a single-line input:

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}> <label> Feedback Laborator: <textarea value={value} onChange={handleChange} /> </label> <button type="submit" value="Submit" /> </form>

Select

In HTML, <select> creates a drop-down list. For example, this HTML creates a drop-down list of our previous labs:

export default function Form() {

const [value, setValue] = React.useState('lab3')

return (

<select value={value} onChange={handleChange}>

<option value="lab1">Lab 1</option>

<option value="lab2">Lab 2</option>

<option value="lab3">Lab 3</option>

<option value="lab4">Lab 4</option>

</select>

);

}

Note that the “Lab 3” option is initially selected, because of its initial state.

Handling Multiple Inputs

When you need to handle multiple controlled input elements, you can add a name attribute to each element and let the handler function choose what to do based on the value of event.target.name.

const MyComponent = () => { const [inputs, setInputs] = useState({ field1: '', field2: '', }); const handleChange = e => setInputs(prevState => ({ ...prevState, [e.target.name]: e.target.value })); return ( <div> <input name="field1" value={inputs.field1 || ''} onChange={handleChange} /> <input name="field2" value={inputs.field2 || ''} onChange={handleChange} /> </div> ) }

Form Validation

Form Validation is the process used to check if the information provided by the user is correct or not (eg: if an email containts '@'). There are two types of validation:

- Client Side: Validation is done in the browser

- Server Side: Validation is done on the server

Client-side validation is further categorized as:

- Built-in: Uses HTML-based attributes like required, type, minLength, maxLength, pattern, etc.

- JavaScript-based: Validation that's coded with JavaScript.

Validation HTML-based attributes:

- required: the fields with this attribute must be filled.

- type: i.e a number, email address, string, etc.

- minLength: minimum length for the text data string.

- maxLength: maximum length for the text data string.

Example:

<form> <label forHtml="feedback">Lab Feedback</label> <input type="text" id="feedback" name="feedback" required minLength="20" maxLength="40" /> <label forHtml="name">Name:</label> <input type="text" id="name" name="name" required /> <button type="submit">Submit</button> </form>

With these validation checks in place, when a user tries to submit an empty field for Name, it gives an error that pops right in the form field. Similarly, the feedback must be between 20 and 40 characters long.

JavaScript-based Form Validation

JavaScript offers an additional level of validation along with HTML native form attributes on the client side.

function validateFormWithJS() { const name = nameRef.current.value; const feedback = feedbackRef.current.value; if (!name) { alert('Please enter your name.') return false } if (feedback.length < 20) { alert('Feedback should be at least 20 characters long.') return false } } return( <form onSubmit={validateFormWithJS}> <label forHtml="feedback">Lab Feedback</label> <input type="text" id="feedback" name="feedback" ref={feedbackRef} /> <label forHtml="name">Name:</label> <input ref={nameRef} type="text" id="name" name="name" required /> <button type="submit">Submit</button> </form> )

React useRef() hook

In most cases, we recommend using controlled components to implement forms. In a controlled component, form data is handled by a React component. The alternative is uncontrolled components, where form data is handled by the DOM itself.

To write an uncontrolled component, instead of writing an event handler for every state update, you can use a ref to get form values from the DOM.

useRef returns a mutable ref object whose .current property is initialized to the passed argument (initialValue). The returned object will persist for the full lifetime of the component.

You might be familiar with refs primarily as a way to access the DOM. If you pass a ref object to React with <div ref={myRef} />, React will set its .current property to the corresponding DOM node whenever that node changes.

function GetTextAreaDataUsingUseRef() { const inputEl = React.useRef(); const onButtonClick = () => { // `current` points to the mounted text input element console.log(inputEl.current.value); }; return ( <div> <input ref={inputEl} type="text" /> <button onClick={onButtonClick}>Focus the input</button> </div> ); }

Promises

The Promise object represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation and its resulting value.

Here, we create a promise that will resolve after 300ms.

const myPromise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { setTimeout(() => { resolve("foo"); }, 300); });

The Promise.resolve() method “resolves” a given value to a Promise. If the value is a promise, that promise is returned; if the value is a thenable, Promise.resolve() will call the then() method with two callbacks it prepared; otherwise the returned promise will be fulfilled with the value.

A Promise that is resolved with the given value, or the promise passed as value, if the value was a promise object. It may be either fulfilled or rejected — for example, resolving a rejected promise will still result in a rejected promise.

const promise1 = Promise.resolve('lab4'); promise1.then((value) => { console.log(value); // expected output: lab4 });

Async/Await

An async function is a function declared with the async keyword, and the await keyword is permitted within it. The async and await keywords enable asynchronous, promise-based behavior to be written in a cleaner style, avoiding the need to explicitly configure promise chains.

async function foo() { await 'lab4'; }

Is similar to:

function foo() { return Promise.resolve('lab4').then(() => undefined); }

The async and await keywords are tools to manage promises.

If you mark a function as async then:

- its normal return value is replaced with a promise that resolves to its normal return value.

- you may use await inside it

If you use await on the left hand side of a promise, then the containing function will go to sleep until the promise settles. Execution outside the async function will continue while it sleeps (i.e. is is not halted).

The await keyword is only valid inside async functions within regular JavaScript code. If you use it outside of an async function's body, you will get a SyntaxError.

Axios

Axios is a promise-based HTTP Client for node.js and the browser. It can run in the browser and nodejs with the same codebase. On the server-side it uses the native node.js http module, while on the client (browser) it uses XMLHttpRequests.

We are gonna use Axios to make HTTP requests.

Example GET Request using AXIOS:

axios.get('https://dummyjson.com/users') .then(function (response) { // handle success console.log(response); });

Example POST Request using AXIOS:

axios.post('https://dummyjson.com/users/add', { firstName: 'Prenume', lastName: 'Dumitrescu', age: 30, /* other user data */ }) .then(function (response) { console.log(response); });

Tasks

- Download the generated project se-lab4-tasks.zip (and run npm install and npm run dev)

- Create a product form:

- Implement the form in component/Form.js, the form should have the following:

- Title (required)

- Description (textarea, optional, length must be at least 30)

- Price (number, required)

- Discount percentage (optional, must be greater than 5%)

- A category selection drop down list (Smartphones/ Laptops etc)

- For the next part we are going to use a public dummy API to simulate HTTP Requests. We are going to use the dummy products api

- Get a list of all products available and display them in any way you want (using a list, a table etc)

- When submitting the form we created above, add a new product through an API call (POST).

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 05 - Next.js: SSR and SSG

Single Page Applications (SPAs)

Classic web pages usually render visual elements on the screen using HTML (to structure the visual elements) and CSS (to style them), while utilizing JavaScript just to make that page interactive (e.g. trigger an action when the user clicks a button, perform error handling for forms, display additional information on hover, etc.).

In contrast, Single Page Applications or SPAs rely heavily on JavaScript for almost everything, including rendering the entire user interface (UI). That is also the case for almost every web development framework (also simply called JavaScript frameworks) out there, including Angular, Vue, and React. React is a telling example, as it uses JavaScript for writing every part of the component, including the template (JSX) and the styling (more on that in future tutorials). When you build a React application to make it ready for production, the JSX template, the styling of the components, and the JS logic are transformed using a compiler (usually Babel) and bundled together into pure JS code and optimized using a dedicated build tool (usually Webpack). The resulting JS resources together with minimal HTML and CSS boilerplate are then served to the browser when the latter performs a GET request.

An advantage of this approach is that the server's response to a client request comprises minimal HTML and CSS code and some JavaScript resources that are usually obfuscated and heavily minified. That leads to faster response times from the server and a pleasing user experience (UX), as the visual elements start to be rendered dynamically as soon as the browser starts executing the JavaScript received from the server. Moreover, when the user navigates through the app, a few requests are further sent to the server as the majority of new visual elements are displayed in the browser by executing even more JavaScript written in the same resources that were initially fetched when the page was initialized.

The big disadvantage however, is that crawlers don't like SPAs. That means that when Google's bots visit your page to index it and then rank it for search results, they usually don't like to wait for the loading and execution of JS code so they can understand what visual elements are in it. And even if the crawlers have become increasingly more performant and JS-tolerant, there is still a problem with semantics. JavaScript frameworks were not designed with semantics in mind. That means that the HTML elements that are dynamically generated at runtime usually don't respect the best practices (e.g. use paragraphs for text content, use headers in hierarchical order, include semantic elements, etc.). That is a big red flag for SEO and solving it just by using React is pretty difficult.

Pre-Rendering (SSR and SSG)

To solve the discussed issues, we can use pre-rendering. That is generating HTML and CSS code in advance, for each page instead of relying solely on the client-side execution of JavaScript. As a result, the amount of JS code executed by the browser is heavily reduced as it is used only for making the page fully interactive. This process is called hydration and a great tool for doing this in React is Next.js.

There are usually 2 types of pre-rending, both being supported by Next.js.

1. Server-Side Rendering (SSR)

In this case, the HTML and CSS code is generated on each request. This is an SEO-friendly approach that is hybrid in nature, as it allows the application to serve different content in a context-dependent fashion while minimizing the amount of JavaSript code that gets executed on the client. Hence, SSR is perfect for scenarios where real-time interactivity (e.g. a live map, live stats display, counter, etc.) is not required, but some parts of the page cannot be determined at build time, but on each HTTP request.

2. Static Site Generation (SSG)

SSG goes one step further and pre-renders the styled HTML at build time. That means that the same content will be returned for every subsequent HTTP request and data on that page will not change whatsoever. This approach is suitable for landing pages, articles, blog posts, or other web pages that solely rely on static content. This pre-rendering technique is highly recommended as it offers huge SEO benefits, but it can also be leveraged by Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) or other caching techniques (e.g. Cloudflare).

SSG Implementation

When generating content at build time, Next.js also supports fetching external data beforehand. That can be performed by defining the getStaticProps inside the file where a page is defined (more on pages later).

export default function Home(props) { return <p>Little known fact: {props.fact}</p>; } export async function getStaticProps() { const fact = getAwesomeFactFromApi(); // These are the same props that are passed as an argument to the component return { props: { fact } }; }

SSR Implementation

Likewise, external data can be fetched at request time, before bundling the web page and returning it to the client. To do that, the getServerSideProps function must be defined in the same file where the page is defined (again, more on pages later).

export default function UserProfile({ firstName, lastName }) { return <p>Hi! My name is {firstName} {lastName}.</p>; } export async function getServerSideProps() { const userId = ... // get the userId somehow (e.g. from the query param) const profileData = fetchUserData(userId); // These are the same props that are passed as an argument to the component return { props: { firstName: profileData.firstName, lastName: profileData.lastName, } }; }

Client-Side Rendering

Conveniently, if the getStaticProps and getServerSideProps are not defined, Next.js will automatically use the SSG approach. However, if further tweaks must be performed exclusively on the client side after the static page is received, that can be done using hooks as one normally does in React.

Next.js recommends fetching data on the client using SWR, a popular React hook just for that.

import useSWR from 'swr'; function Dashboard() { // "fetcher" can be Axios const { dashboardData, error } = useSWR('/api/dashboard/stats', fetcher); if (error) return <p>An error occurred!</p>; if (!dashboardData) return <div>Loading dashboard data...</div>; return ( <div> <h1>My Dashboard</h1> <p>Visitors: {dashboardData.visitors}</p> <p>CPU usage: {dashboardData.cpu}%</p> <p>Memory usage: {dashboardData.memoryMB}MB</p> </div> ); }

Next.js Routing

Next.js has an opinionated way of handling the application routes. Each .js, .jsx, .ts, or .tsx file that sits in the pages directory represents a page and from a React perspective, it is just another component. However, these are the only files in which the getServerSideProps and getStaticProps functions can be written to inform Next.js whether those pages are using SSR or SSG.

By default, each directory represents a part of the resulting URL of your page. That also applies to those files whose names are not index. Hence, the following structures are equivalent:

* pages/index.jsx * pages/blog/index.jsx * pages/blog/first-post/index.jsx

* pages/index.jsx * pages/blog/index.jsx * pages/blog/first-post.jsx

And they both generate the URLs:

* / * /blog * /blog/first-post

Dynamic Routes

Next.js also supports dynamic routes which are useful when the route depends on a URI parameter. Here are some examples of URLs where this might come in handy:

* /blog/:post-name * /profile/:user-id * /videos/:video-id/statistics * /questions/*

In these cases, square brackets are used in the naming of files or directories to indicate that the route is dynamic:

* /blog/[post-name].jsx * /profile/:[user-id].jsx * /videos/[video-id]/statistics.jsx * /questions/[...all].jsx

Page Linking

To link pages together, Next.js provides you with a dedicated component called Link, which works similarly to the classic anchor tag.

import Link from 'next/link'; function Home({ otherBlogPosts }) { return ( <ul> <li> <Link href="/">Home</Link> </li> <li> <Link href="/blog">Thoughts</Link> </li> <li> <Link href="/blog/first-post">How the story beginned</Link> </li> {otherBlogPosts.map((post) => ( <li key={post.id}> <Link href={`/blog/${encodeURIComponent(post.path)}`}> {post.name} </Link> </li> ))} </ul> ) } export default Home;

As an alternative, if you want to navigate between pages dynamically, from your JavaScript logic, you can do that with useRouter.

import { useRouter } from 'next/router'; function Blog({ completePostpath }) { const router = useRouter(); const handleClick = () => router.push(completePostpath); // e.g. /blog/first-post return ( <div> <p>Welcome!</p> <button onClick={handleClick}>My first blog post</button> </div> ) } export default Blog;

Disable SSR/SSG

Next.js also allows you to disable the default behavior of pre-generating the HTML and CSS code at build time by explicitly indicating that you want to dynamically load a certain component on the client side. The rendering of that component will be performed by executing JavaScript code in the browser, just like it happens with a classic SPA. This approach might be useful when you need to access client-side specific libraries (e.g. window).

import dynamic from 'next/dynamic'; const DynamicHeader = dynamic(() => import('../components/header'), { ssr: false, }); function Home() { return ( <div> <DynamicHeader/> <h1>Welcome to my page!</h1> </div> ) } export default Home;

Layouts

If you want to reuse components on multiple pages, layouts come in handy. For instance, your app might have a header and a footer on each page:

// layouts/layout.jsx import Navbar from '..components/navbar'; import Footer from '..components/footer'; export default function Layout({ children }) { return ( <> <Navbar /> <main>{children}</main> <Footer /> </> ); }

// pages/_app.jsx import Layout from '../layouts/layout'; export default function Home({ Component, pageProps }) { return ( <Layout> <Component {...pageProps} /> </Layout> ); }

Multiple layouts can also be used on a per-page basis. You can find more about that here.

Next.js Configuration

There is a plethora of configurations supported by Next.js that can be written in the next.config.js file which resides at the root of your project. One can set environment variables, base paths for routes, internationalization, CDN support, path reroutes, etc. You can find more about that here.

Tasks

For this project, we will use the Cat Facts API. The GET requests will be performed using Axios.

- Download the project archive for this lab and run npm install and npm run dev.

- Link the home page and the /tasks page together (the tasks page should be reachable from the home page and vice-versa).

- Create an SSR page at /cats that displays 3 random cat facts. Use a dedicated Fact component.

- Create an SSG page at /cats/breeds that displays the first 10 breeds in alphabetic order. Use a dedicated Breed component.

- Create a layout for your entire application that adds a header containing a cat logo for all of your pages (you already have the logo in the public directory).

- Link the homepage with the /cats page using the Link component and the /cats/breeds page using the useRouter hook.

- Create a page at /dynamic-tasks that is identical to the /tasks page, but it loads the TasksList component dynamically, on the client side.

- Build your application using npm run build and then start your production-ready application using npm run start.

- Open the /tasks and /dynamic-tasks pages on 2 separate tabs and inspect the page sources for both of them. Discuss your findings with the assistant.

- Create a custom 404 page (see this guide).

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 06 - Analytics

Introduction

After you manage to bring the first users to your product it becomes very important to look at how they are using it in order to gain insights about how to improve it. This is where analytics tools come in. With these modern tools you can track everything your users do in both a quantitative and a qualitative way so that you can then use this data to improve your product.

In this lab we are going to look at two excellent tools as well as a data platform to help you manage the data you send to these tools.

First, we are going record some events using Segment. This will act as a central hub for our user event data.

Then we are going to hook up Amplitude for quantitative analytics and Fullstory for screen recordings.

1. Segment

Segment is a tool that collects events from your app and provides a complete data toolkit. It gives you a uniform API to send event data to all the other tools we'll be using. This way you only have to integrate the data collection once, and Segment will then forward that data to all the other analytics tools you want to use.

For the purposes of this lab you will need to add a JS source to segment which will be represented by our Next.js app. The most elegant way to do this for Next.js is via the @segment/snippet npm plugin.

Add the package to your project.

npm install --save @segment/snippet

Then include the script in our Next.js app by creating _document.jsx under your pages directory.

import Document, { Html, Head, Main, NextScript } from 'next/document'

// import Segment Snippet

import * as snippet from '@segment/snippet';

class MyDocument extends Document {

renderSnippet() {

const opts = {

apiKey: 'YOUR-SEGMENT-API-KEY',

page: true

}

return snippet.max(opts);

}

static async getInitialProps(ctx) {

const initialProps = await Document.getInitialProps(ctx)

return { ...initialProps }

}

render() {

return (

<Html>

<Head>

{/* Inject the Segment snippet into the head of the document */}

<script dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: this.renderSnippet() }} />

</Head>

<body>

<Main />

<NextScript />

</body>

</Html>

)

}

}

export default MyDocument

Use the Segment debugger to know if your app actually connects to Segment.

Your will now be able to call Segment functions like global.analytics.track(). Check out the Segment docs for details here.

For this lab we will want to use Track to know when a user clicked on a task and Identify to associated some user details to the tracked events in order to know who did what.

2. Amplitude

Amplitude is a great tool for understanding user event data in a quantitative way. You can easily build many types of charts like product funnels, retention charts, or north star metrics charts.

3. Fullstory

Fullstory is a great tool to understand your user event data in a more qualitative way via its screen recording feature. This can be used to understand exactly how users interact with your user interface every step of the way.

Tasks

Use the app you built in the previous lab as a starting point: se-lab5-slutions.zip

1. Configure the app so that it sends data to Segment. Add Track and Identify events and make sure your see them in the Segment debugger for your source.

2. Connect Segment to Amplitude and create some charts for task click events. Then try to creare a funnel: main page > tasks page > task click.

3. Connect Segment to Fullstory and view a screen recording.

4. [Bonus] Install Google Analytics without using Segment

1. Run your app in incognito mode to avoid any interference from browser plugins like ad blockers that might prevent event data from being sent to Segment.

2. Try doing a shift+refresh to force a hard page refresh of your app (no use of cached JS files). In some cases, after you make some changes to the Segment config, this might be needed.

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 07 - Styling & A/B Testing

CSS Styling

Next.js has support for native .css files that can be applied globally or at the component level.

Global Styling

pages/_app.js is the default app component used by Next.js to initialize each page. It is the starting point of all page components and acts as a blueprint for your pages. Consequently, if you want to apply global styling to your Next.js application, the stylesheets (.css files) must be included here.

/* styles/globals.css */ body { font-family: 'Roboto', 'Helvetica Neue', 'Helvetica', sans-serif; padding: 20px 20px 60px; margin: 0 auto; background: white; }

// pages/_app.jsx import '../styles.css' export default function MyApp({ Component, pageProps }) { return <Component {...pageProps} />; }

Component Styling

To add component-level CSS, we must use CSS modules. These are files that use the [name].module.css naming convention, can be imported anywhere in the application and help you scope the stylesheet to a particular component.

/* components/DangerousButton.module.css */ .danger { color: white; background-color: red; } .danger:hover { color: red; background-color: white; }

For instance, we can use the CSS module to add custom styles to a Material UI button.

// components/DangerousButton.jsx import styles from './DangerousButton.module.css' import { Button } from "@mui/material"; export function DangerousButton(props) { return ( <Button type="button" className={styles.danger} {...props}> { props.children } </Button> ) }

In this case, props.children is a special property that allows us to further pass the content inside the DangerousButton tag into the inner Button tag.

JS Styling

As an alternative to the classic CSS styling, Next.js offers a variety of solutions to style your React components using JavaScript:

- Inline Styles

While the majority of these solutions are provided through 3rd party libraries, inline styles and styled jsx are available out of the box.

Inline Styles

To apply inline styling, we must use the style property.

// components/DangerousTypography.jsx import { Typography } from "@mui/material"; export function DangerousTypography(props) { return ( <Typography {...props} style={{ color: 'red' }}> {props.children} </Typography> ); }

Styled Components

Styled Components is one of the most popular libraries for adding style to your React components. It can be used globally or at the component level. However, we will only discuss the component-level styling with this library.

Conveniently, Material UI natively supports styled components, so we can easily use this library to overwrite the default styling of the MUI components.

// components/CoolCheckbox.jsx import * as React from 'react'; import { styled } from '@mui/material/styles'; import Checkbox from "@mui/material/Checkbox"; const StyledCheckbox = styled(Checkbox)` color: green!important; `; export default function CoolCheckbox({ props }) { return <StyledCheckbox {...props}/>; }

A/B Testing

A/B testing is an accurate method of testing a particular idea, strategy or feature by performing user bucketing and simultaneously delivering two or more sources of truth to these buckets. Such solutions are usually integrated with analytics tools, so you can later assess which source of truth renders the best results.

Let's take a concrete example. You want to display 2 different versions of a button to your users - a blue one and a green one. You want to distribute this experiment evenly among your users, so you would like half of your users to see the green button and the other half the blue one. Moreover, you want this behaviour to be sticky. That means that if a user sees a green button once, they must keep seeing it green until the experiment is over. In the end, we would like to calculate the conversion rate of that particular button, so we need to track each click and record the version of the button (green or blue) for such click. Then, we must wait a sufficient amount of time so we have statistically relevant data for our conversion rate comparison. The winning button will be kept and the other one discarded.

Fortunately, there are 3rd party solutions that allow us to perform such an experiment easily. One of them is Flagsmith and we chose it for this lab because it offers a free plan.

Feature Flags

Flagsmith allows the creation of feature flags, which are the cornerstones of A/B testing. They act as toggle buttons that turn various features on and off.

A/B Testing

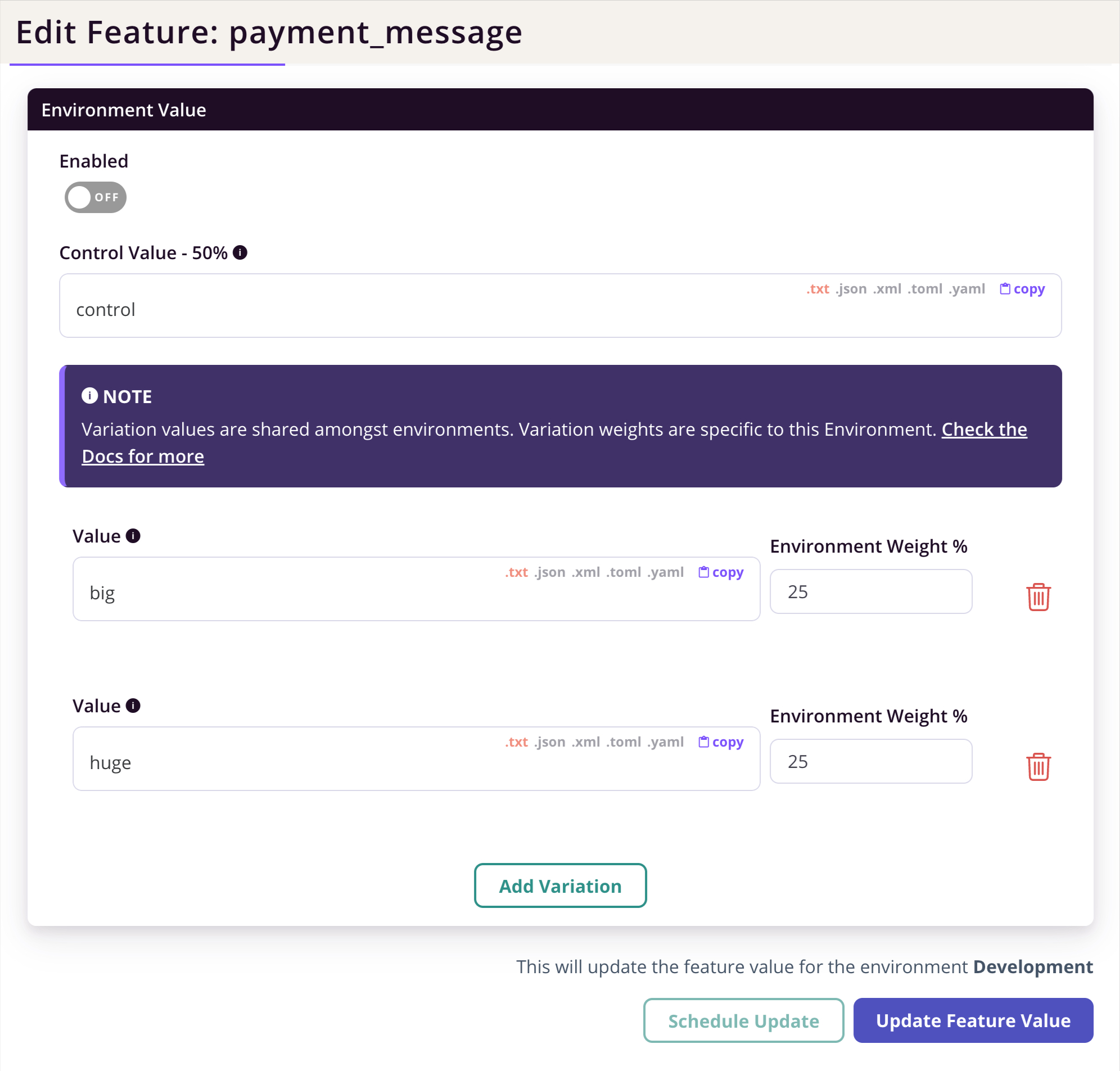

To use feature flags for A/B testing, however, we need to make them multi-variate. That means that our feature flags support variations, and each variation has a particular value assigned to it. The control value is the default value that gets sent to your application if the user is not yet identified (more on that later). Finally, these values can be weighted so you can decide the percentage of users that should participate in the experiment.

Users

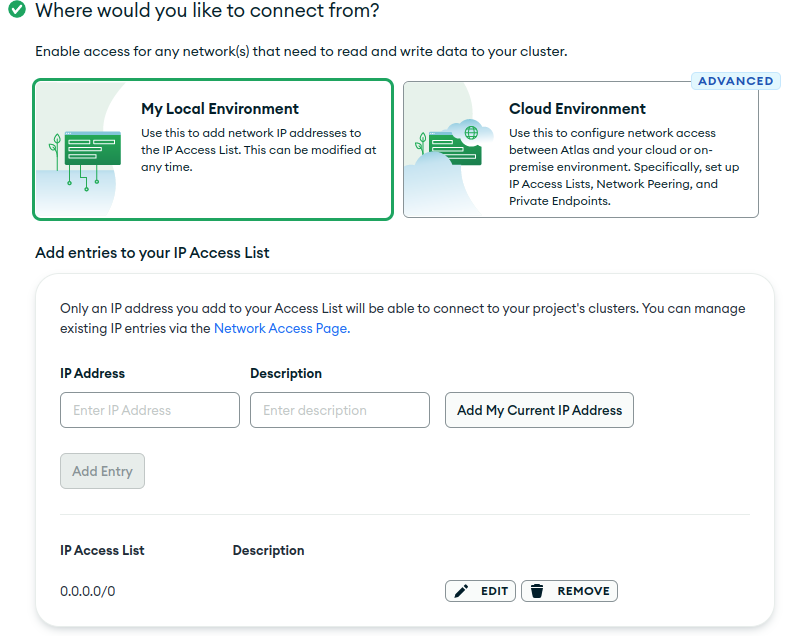

Just like Segment, Flagsmith requires users to be identified. That means that an explicit id must be provided for the user that currently uses the application. If we don't explicitly inform Flagsmith about the user's identity, that user will be considered anonymous and a random id will be assigned internally. Even though feature flags continue to work just fine for both identified and unidentified users, A/B testing can only be performed on identified users. That means that if an unidentified user uses our application, they will always see the feature version corresponding to the control value. In addition to the control value, the identified users can also see the weighted variations.

Users can also have traits and they are useful when you want to perform user segmentation. For instance, you can choose to perform an A/B test only for males, who have premium subscriptions and are at least 21 years old.

If you click on a user from the Users table, you can inspect its traits, manually delete them or add new ones, toggle features for that particular user or even change the values of those features. That can be really useful if you have a development account that you use to test different functionalities.

Next.js Integration

Flagsmith has native support for Next.js, as it can run both on the client and server sides.

Initialization

The initialization code must be written in the pages/_app.jsx component on both the client-side and server-side, so the flags can be then accessed by all pages.

// pages/_app.jsx import * as React from 'react'; import Head from 'next/head'; import Layout from '../layouts/layout'; import '../styles/globals.css'; import flagsmith from "flagsmith/isomorphic"; import { FlagsmithProvider } from "flagsmith/react"; const FLAGSMITH_OPTIONS = { environmentID: 'YOUR_ENVIRONMENT_ID_HERE', enableAnalytics: true, preventFetch: true } MyApp.getInitialProps = async () => { await flagsmith.init(FLAGSMITH_OPTIONS); return { flagsmithState: flagsmith.getState() } } export default function MyApp({ Component, pageProps, flagsmithState }) { return ( <FlagsmithProvider serverState={flagsmithState} flagsmith={flagsmith} options={FLAGSMITH_OPTIONS}> <Head> <title>Lab 7</title> <meta name="description" content="This is the styling and A/B testing lab."/> <meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1, width=device-width"/> </Head> <Layout> <Component {...pageProps} /> </Layout> </FlagsmithProvider> ); }

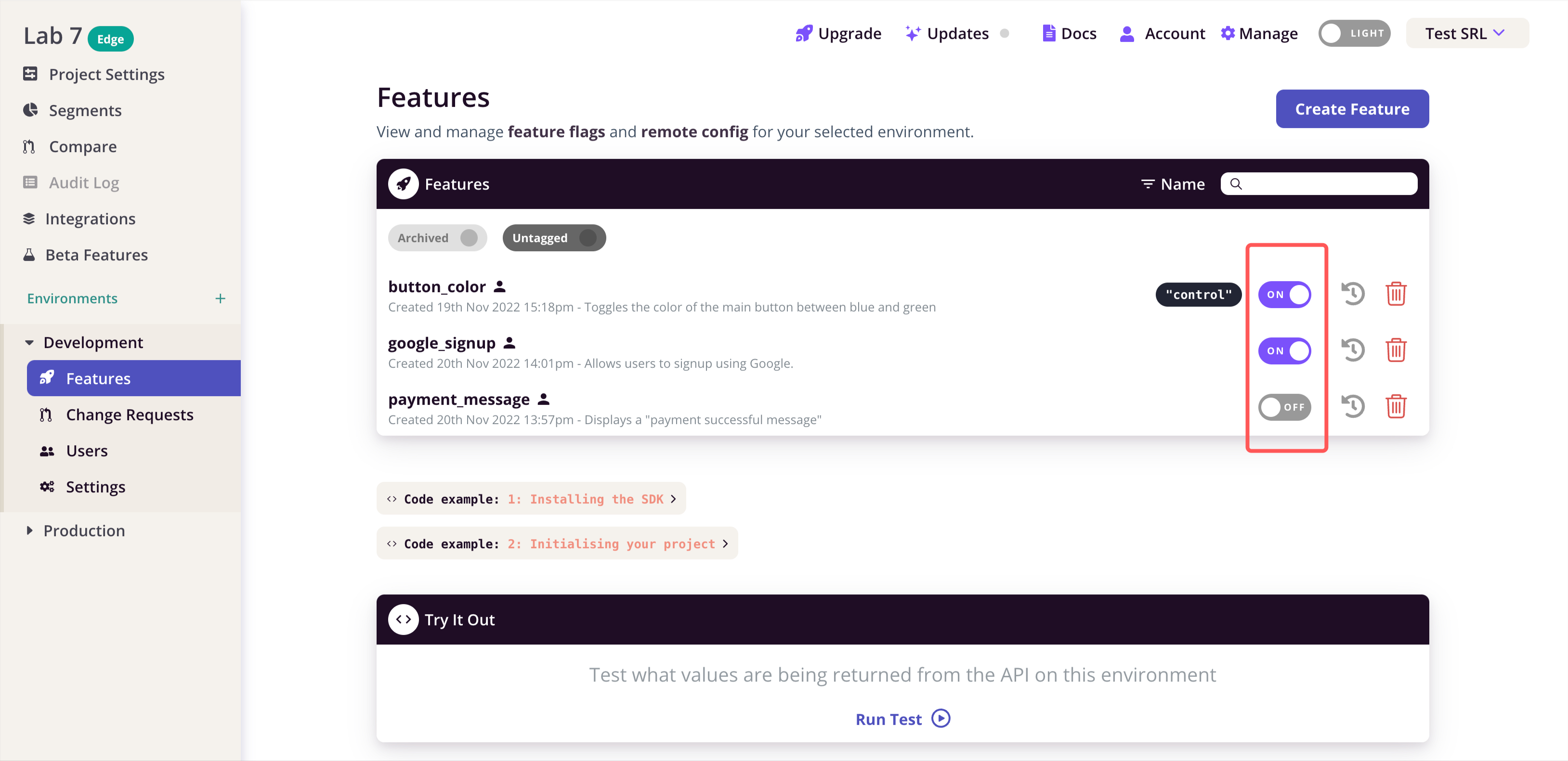

Feature Flags

Feature flags can then be accessed right from the React components.

// pages/index.jsx import React from 'react'; import { Container, Typography } from "@mui/material"; import { useFlags } from "flagsmith/react"; export default function Home() { const flags = useFlags(['google_signup', 'payment_message']); const isGoogleSignupEnabled = flags['google_signup']?.enabled; const paymentMessageSize = flags['payment_message']?.value; // 'big', 'huge' or 'control' return ( <Container maxWidth="sm"> <Typography variant="p" component="p"> Is Google signup enabled: {isGoogleSignupEnabled} </Typography> <Typography variant="p" component="p"> Payment message size: {paymentMessageSize} </Typography> </Container> ); }

Users

Because we don't have a login system integrated into our app, we will identify a fictional user right after the app initialization code.

// pages/_app.jsx MyApp.getInitialProps = async () => { await flagsmith.init(FLAGSMITH_OPTIONS); await flagsmith.identify( 'user_90619', { fullName: 'Marie Curie', email: 'marie.curie@gmail.com', age: 23, gender: 'female', isPremiumUser: false } ); return { flagsmithState: flagsmith.getState() } }

Tasks

The app uses the Cat Facts API and the GET requests are performed using Axios.

The necessary dependencies for the Styled Components and Flagsmith are also included in the project.

- Create a blue button using Styled Components in

components/styled/BlueButton.jsx. - Create a green button using CSS modules in

components/vanilla/GreenButton.jsx. Add the corresponding CSS module in the same directory. - Make the welcome message of the

pages/index.jsxpage component bold using inline styling. - Integrate the global styling written in the

styles/globals.cssfile into the app and remove the horizontal and top padding. - Create a free Flagsmith account, set up a fictive organisation and a project called Lab 7.

- Create a feature in the Development environment called button_color. Create two variations. Give a default value to the control state and suggestive values to the variations (these values should describe the button colours). The weighting should be 50-50 (the control value should have weight 0).

- Write your environment id and place the user identification code in

pages/_app.jsx. - Conditionally display the See Tasks button in

pages/index.jsx. If the button_color feature flag is disabled, it should be aDangerousButton. Conversely, the button should be aGreenButtonorBlueButtondepending on the feature flag value. - Observe how the button changes when you start identifying new users. Check the Users table in the Flagsmith dashboard as well.

Feedback

Please take a minute to fill in the feedback form for this lab.

Lab 08 - Backend

Introduction

In this lab we are going to get comfortable coding in Javascript and learn how to create a backend RESTful web service that can talk to a database.

By the end of this lab, you should have a basic understanding of how to build a simple 3-tier web application consisting of these three layers:

- Frontend (or client/browser)

- Backend (or server)

- Storage (or database)

The stack we are going to use is called MERN. MERN stands for MongoDB, Express, React, NodeJS.

- MongoDB — document database

- ExpressJS — NodeJS web framework

- ReactJS — a client-side JavaScript framework

- NodeJS — JavaScript web server

The previous lab taught you how to use Javascript and frameworks such as React to build the Client. This lab will focus on how to build a backend service and how to connect it to a database.

We are mainly going to be using technologies from the Javascript ecosystem, so in our case we will be using React JS for the frontend, Node JS + Express for the backend, and Mongo DB for the storage.

Setting up your environment

If you have not done so already, please install Node, NPM, and a code editor like VS Code or Atom by following the instructions on their websites.

Node JS

NodeJS is the Javascript runtime that allows us to run Javascript on the server. Any server code you will write in Javascript will run on top of Node so it's a good idea to get a basic understanding of node before attempting to build anything with it.

Go through the first 6 sections of this tutorial:

$ npm install -g learnyounode # use sudo if you run into permission issues $ learnyounode

Express

Express JS is a server framework that allows you to quickly build a RESTful backend on top of Node JS.

Let's write a simple hello world service using Express. Create a new server directory and follow the next steps:

- Use

npm init

- Install express using

npm install --save express

- Create a new index.js file inside your server directory and paste the following code inside: